Regulation of pseudorabies virus infectivity by the host factor NPSR

-

摘要:目的

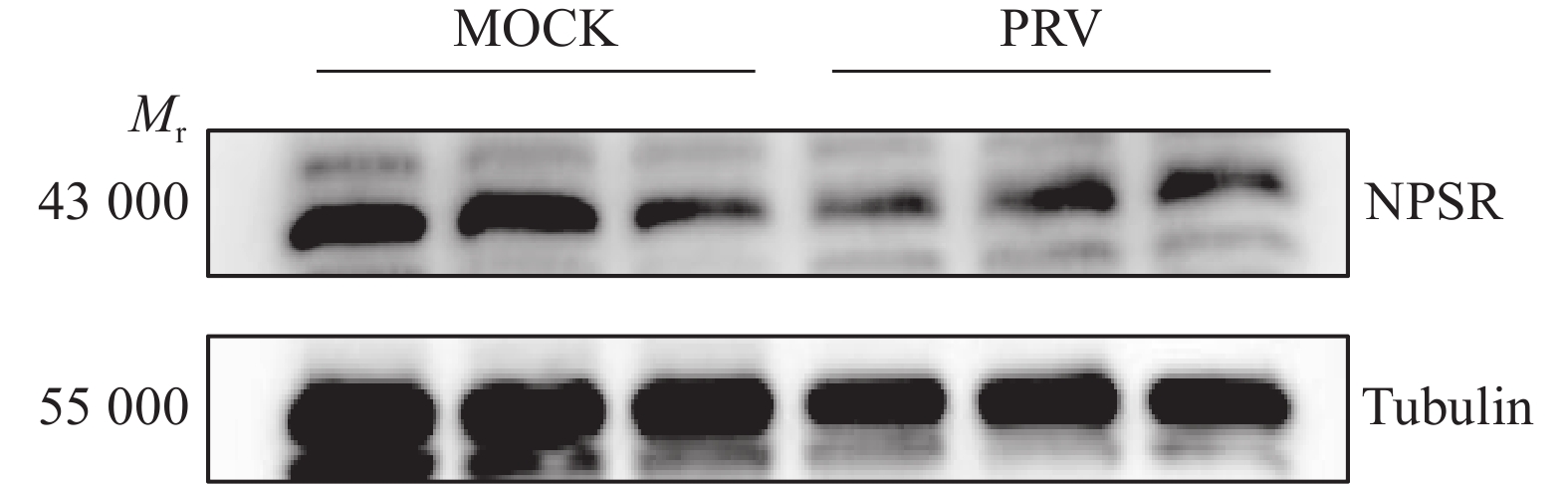

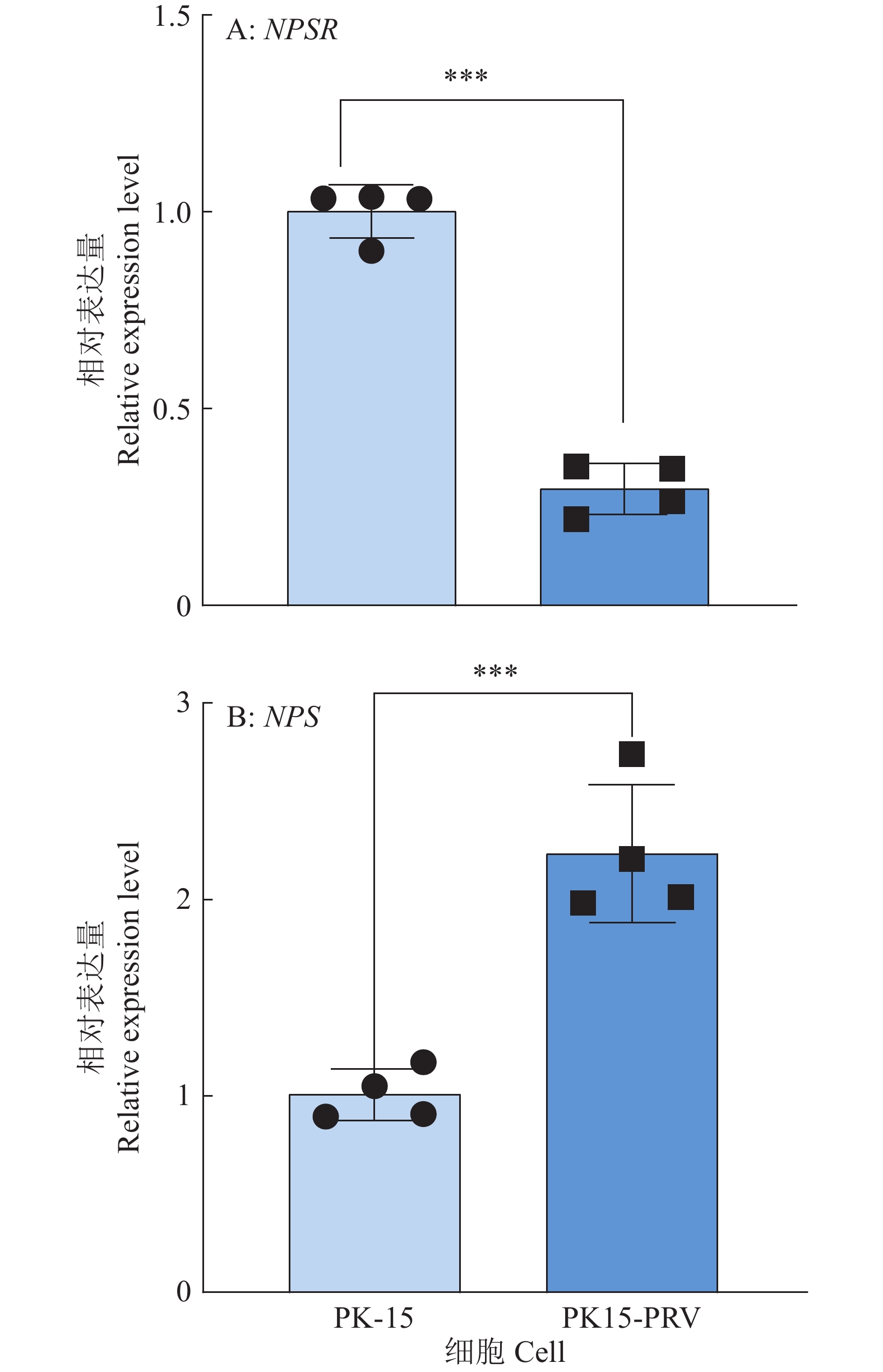

伪狂犬病病毒(Pseudorabies virus,PRV)属甲型疱疹病毒科,是一种嗜神经性病毒,通过接触传播感染造成神经和呼吸系统疾病。猪是PRV的自然宿主,PRV的感染和流行对养猪业造成巨大经济损失。PRV侵染宿主中枢神经系统后,引发神经肽S(Neuropeptide S,NPS)系统表达水平的改变。NPS是一种神经肽物质,作为神经内分泌系统的关键成员在中枢神经系统中广泛分布,与慢性疾病相关联,NPS通过神经肽S受体(Neuropeptide S receptor,NPSR)介导多样化的生理功能,在机体内以NPS/NPSR系统形式共同参与神经内分泌−免疫网络调节。本研究探讨了NPS/NPSR系统在PRV感染宿主细胞中的作用,以期待开发新的抗PRV靶点。

方法通过CRISPR/Cas9构建NPS和NPSR敲除的PK15细胞系,利用qPCR、免疫荧光、Western blot、免疫共沉淀(CO-IP)等方法检测感染PRV病毒后细胞系的抗病毒能力及NPSR与病毒表面糖蛋白的结合能力。

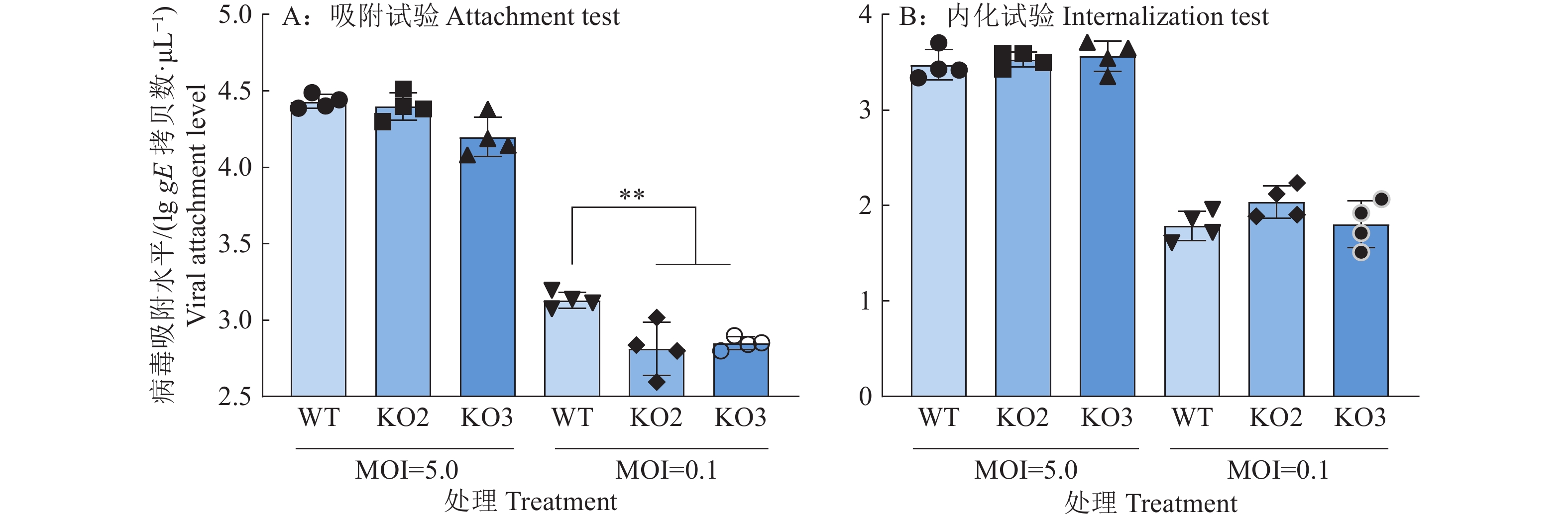

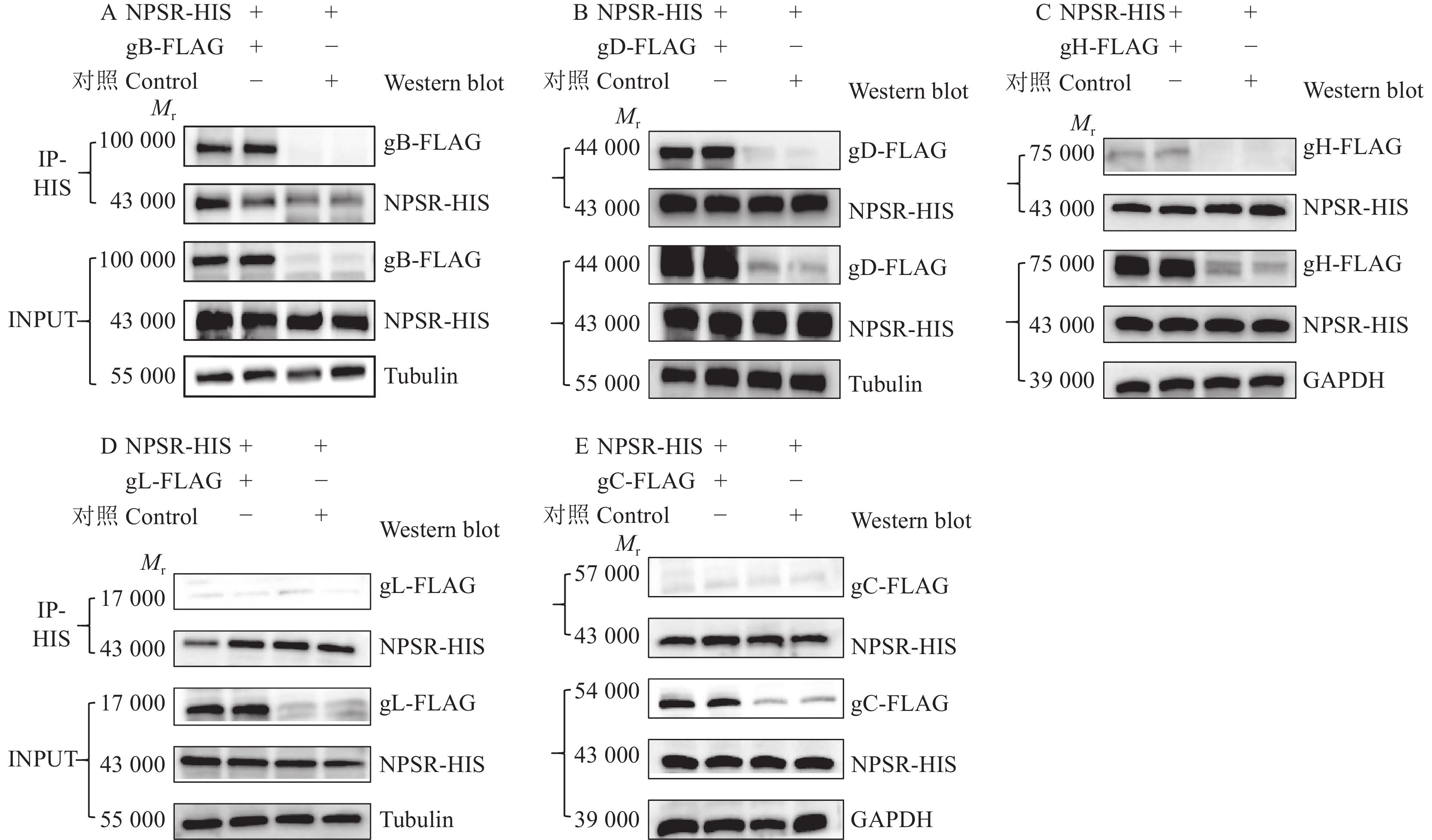

结果NPSR敲除能减弱PRV对PK15细胞的感染能力,而NPS基因敲除增强了PRV对PK15细胞的感染能力。NPSR敲除细胞在PRV吸附过程中能减少病毒的侵入量,因此NPSR是潜在的PRV入侵受体。CO-IP试验证明,NPSR与病毒包膜蛋白gB和gD存在相互作用。

结论NPSR通过与病毒表面糖蛋白结合促进PRV感染,NPSR可能是PRV感染神经系统的受体因子之一。NPSR敲除能显著抑制PRV对PK15细胞的感染。NPSR可为开发PRV防控药物和治疗策略提供新的研究靶点。

Abstract:ObjectivePseudorabies virus (PRV), belonging to the herpesviridae family, is a neurotropic virus that spreads infection and causes neurological and respiratory diseases through contact. Pigs are the natural hosts of PRV, and PRV infections and epidemics cause great economic losses to the pig industry. PRV infection of the host central nervous system triggers changes in the expression level of the neuropeptide S (NPS) system, a neuropeptide substance that is widely distributed in the central nervous system as a key member of the neuroendocrine system, and is associated with chronic diseases. NPS mediates diverse physiological functions through the neuropeptide S receptor (NPSR), which participates in the regulation of the neuroendocrine-immune network in the body as the NPS/NPSR system together. In this study, we investigated the role of the NPS/NPSR system in PRV-infected host cells in anticipation of developing new anti-PRV targets.

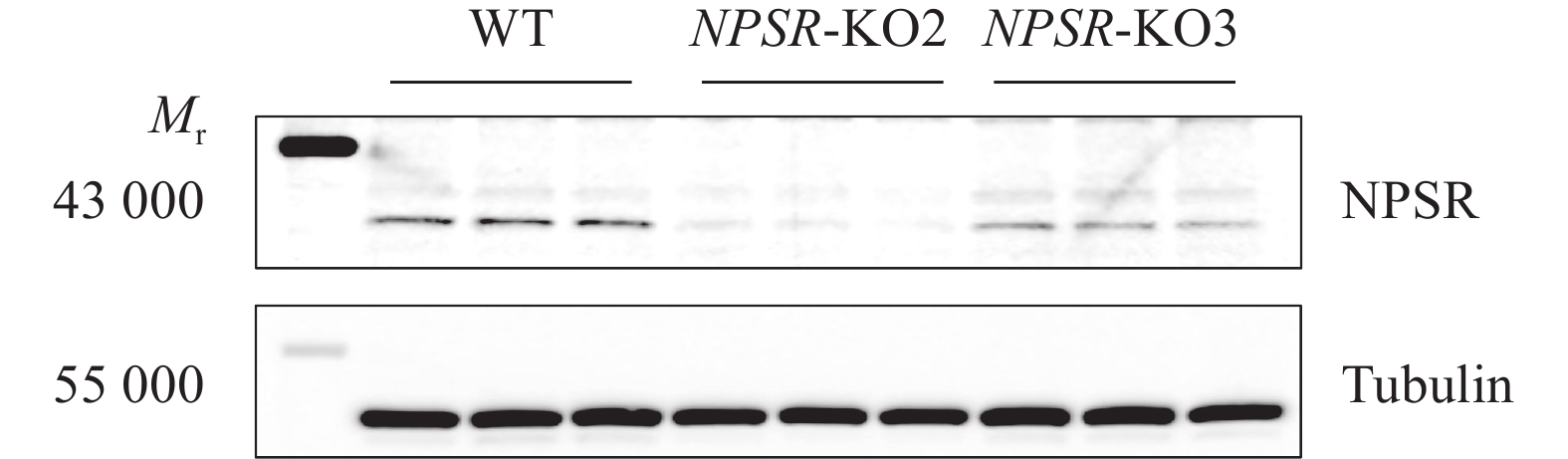

MethodNPS and NPSR knock-out PK15 cell lines were constructed by CRISPR/Cas9 method. The antiviral ability of cell lines infected with PRV virus and the binding ability of NPSR to viral surface glycoproteins were detected by qPCR, immunofluorescence, Western blot and co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP).

ResultNPSR knockout attenuated the infectivity of PRV on PK15 cells, while NPS knockout enhanced the infectivity of PRV on PK15 cells. NPSR knockout cells reduced viral invasion during PRV adsorption, thus NPSR was a potential PRV invasion receptor. The interaction of NPSR with viral envelope proteins gB and gD were demonstrated by CO-IP experiment.

ConclusionNPSR promotes PRV infection by binding to viral surface glycoproteins, and NPSR may be one of the receptor factors for PRV infection of the nervous system. NPSR knockout significantly inhibits the infection of PK15 cells by PRV. NPSR may provide new research targets for the development of drugs and therapeutic strategies for PRV prevention and control.

-

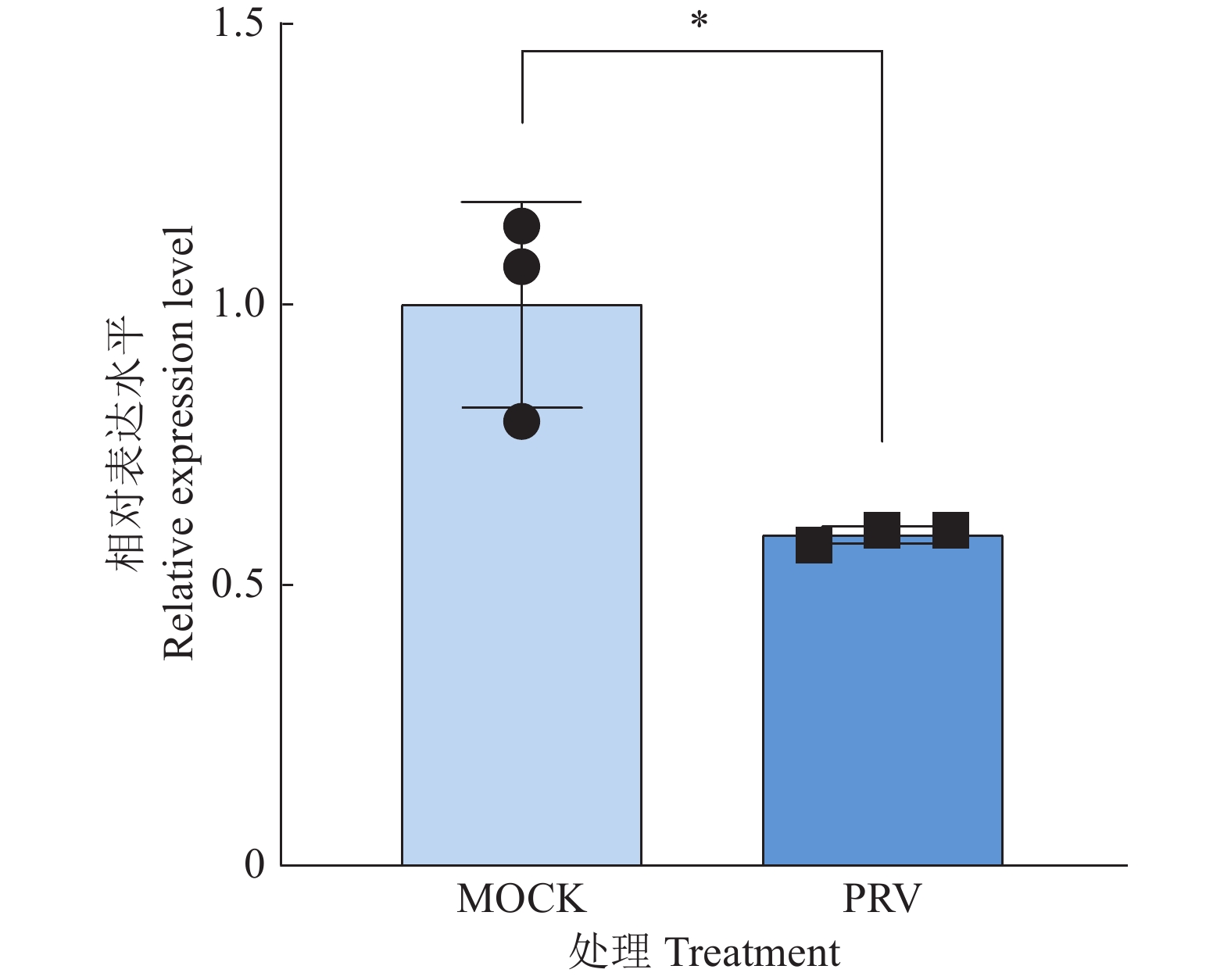

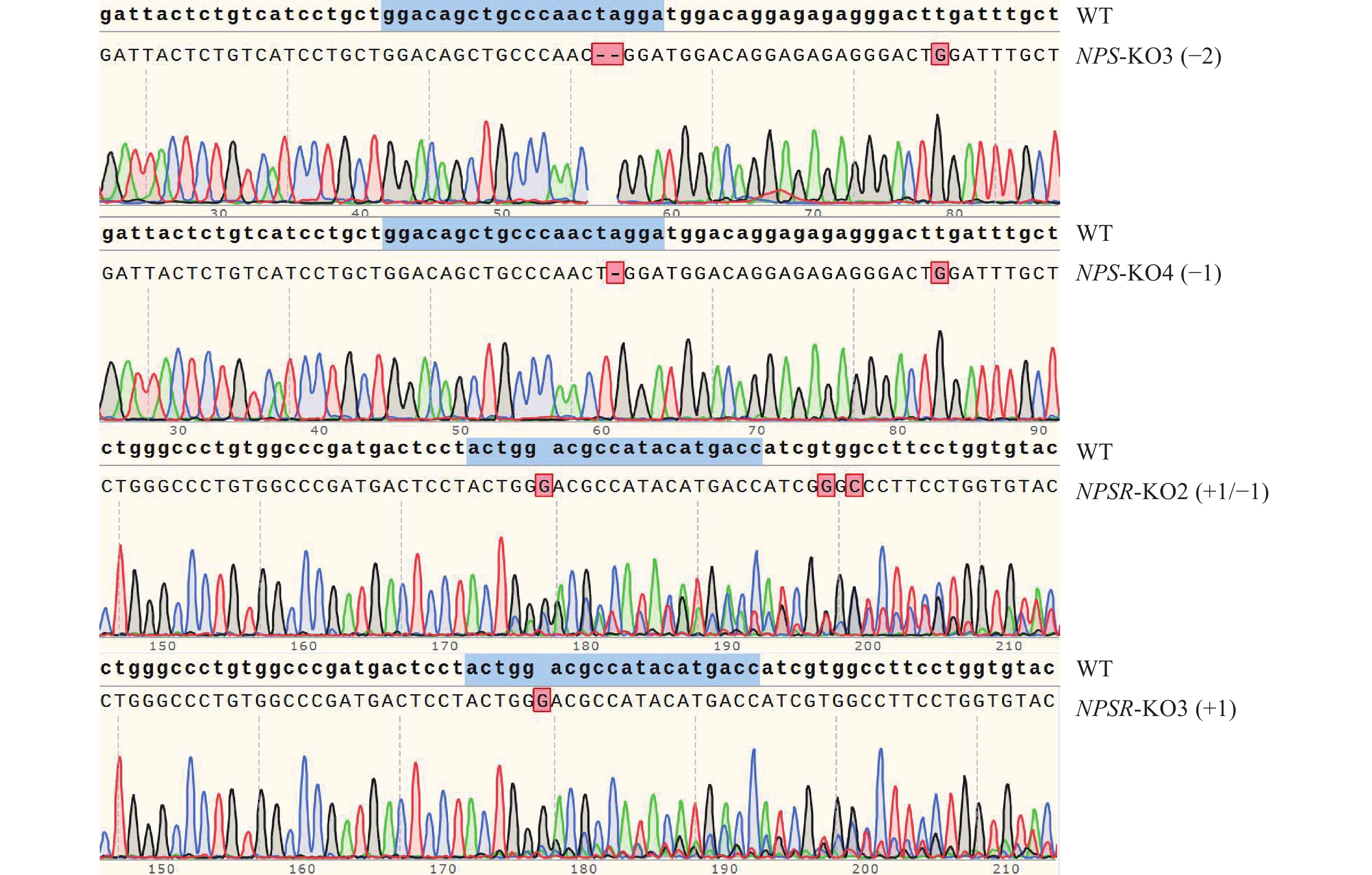

图 4 NPS及NPSR阳性克隆细胞的靶点序列测序图谱

蓝色记号部分为sgRNA序列,+/−表示增加或缺失相应数量碱基,仅选取部分测序图谱作为展示

Figure 4. Target sequencing of NPS and NPSR knockout positive cells colonies

The blue markers are sgRNA sequences, +/− indicates adding or missing the corresponding number bases, and only some sequencing profiles are selected for demonstration

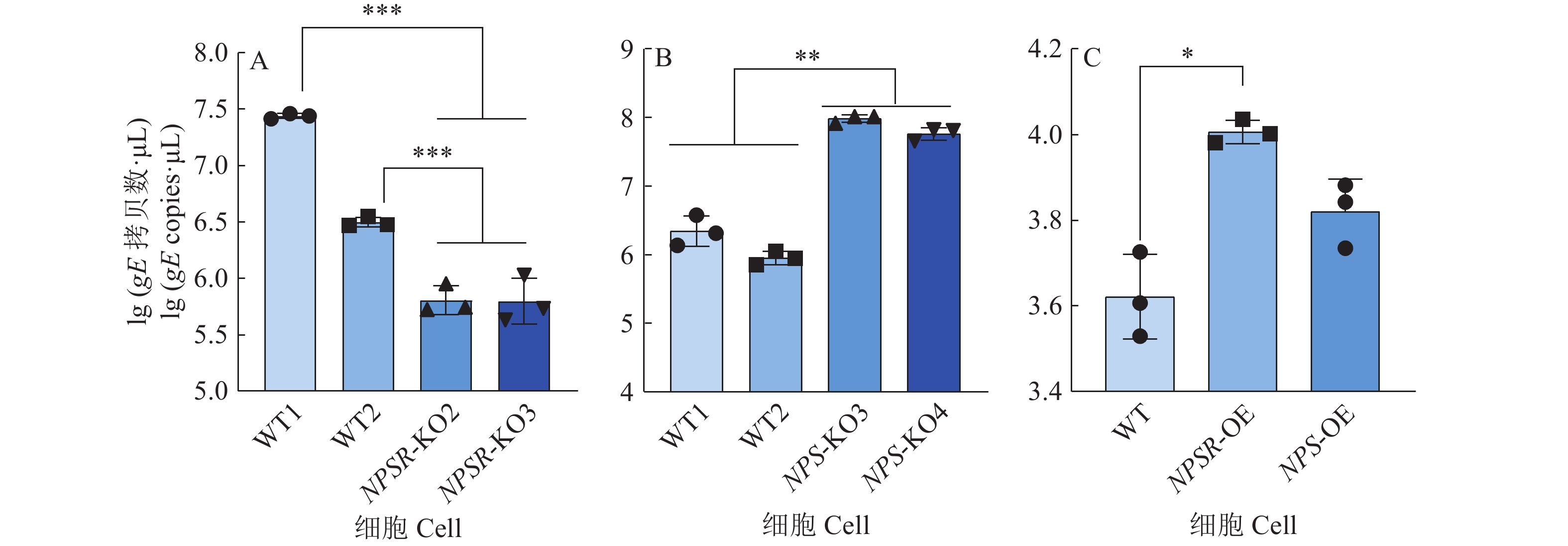

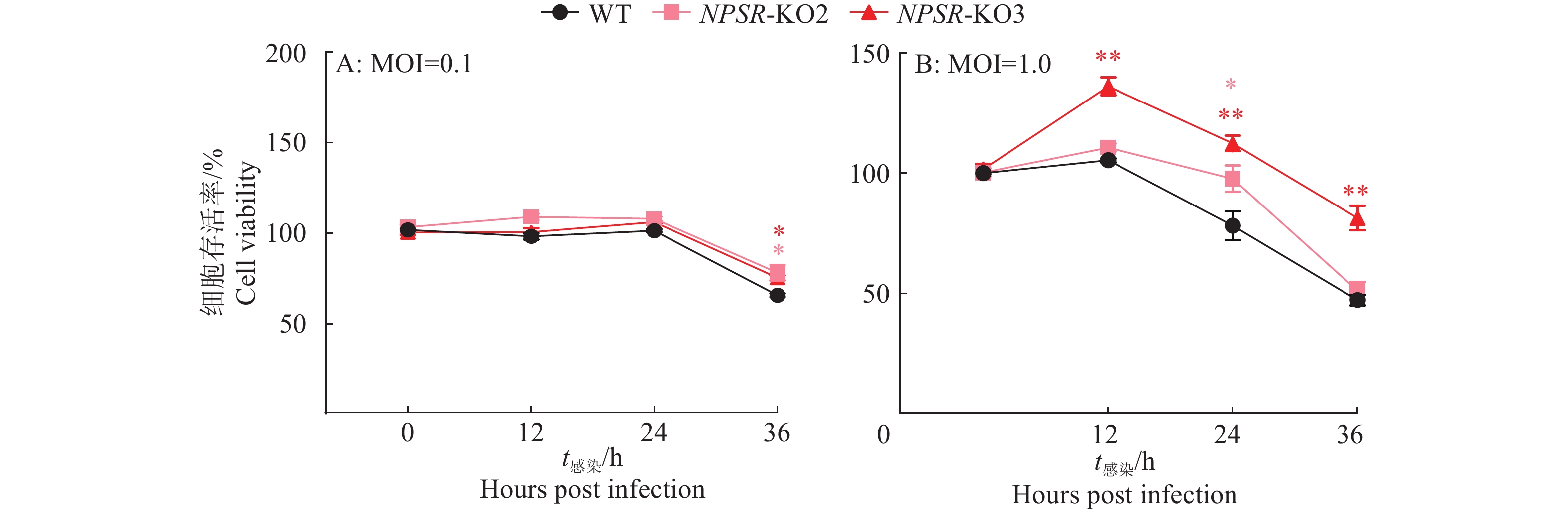

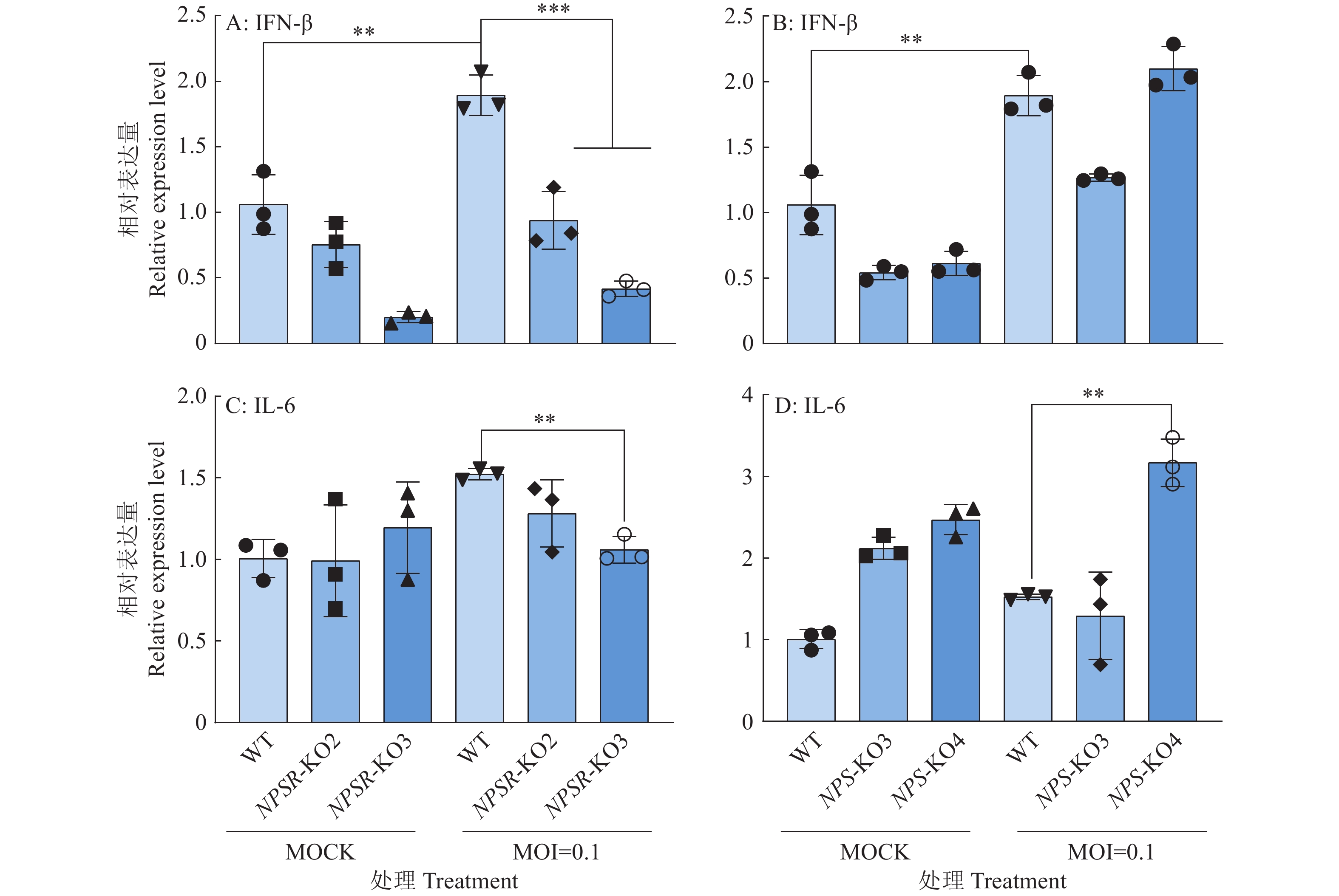

图 6 NPS及NPSR基因敲除和过表达后PRV在PK15细胞内的复制水平

图A、B中,WT1和WT2为经过与敲除细胞相同的筛选流程而未突变的PK15细胞系;图C中,WT为纯野生型细胞;“*”“**”“***”分别表示在P < 0.05、P < 0.01、P < 0.001水平差异显著(t检验)

Figure 6. PRV replication level in PK15 cells after NPS and NPSR knockout and overexpression

In figure A and B, WT1 and WT2 are unmutated PK15 cell lines that underwent the same screening process as the knockout cells; In figure C, WT are pure wild-type cells; “*” “**” “***” indicate significant differences at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 levels respectively (t test)

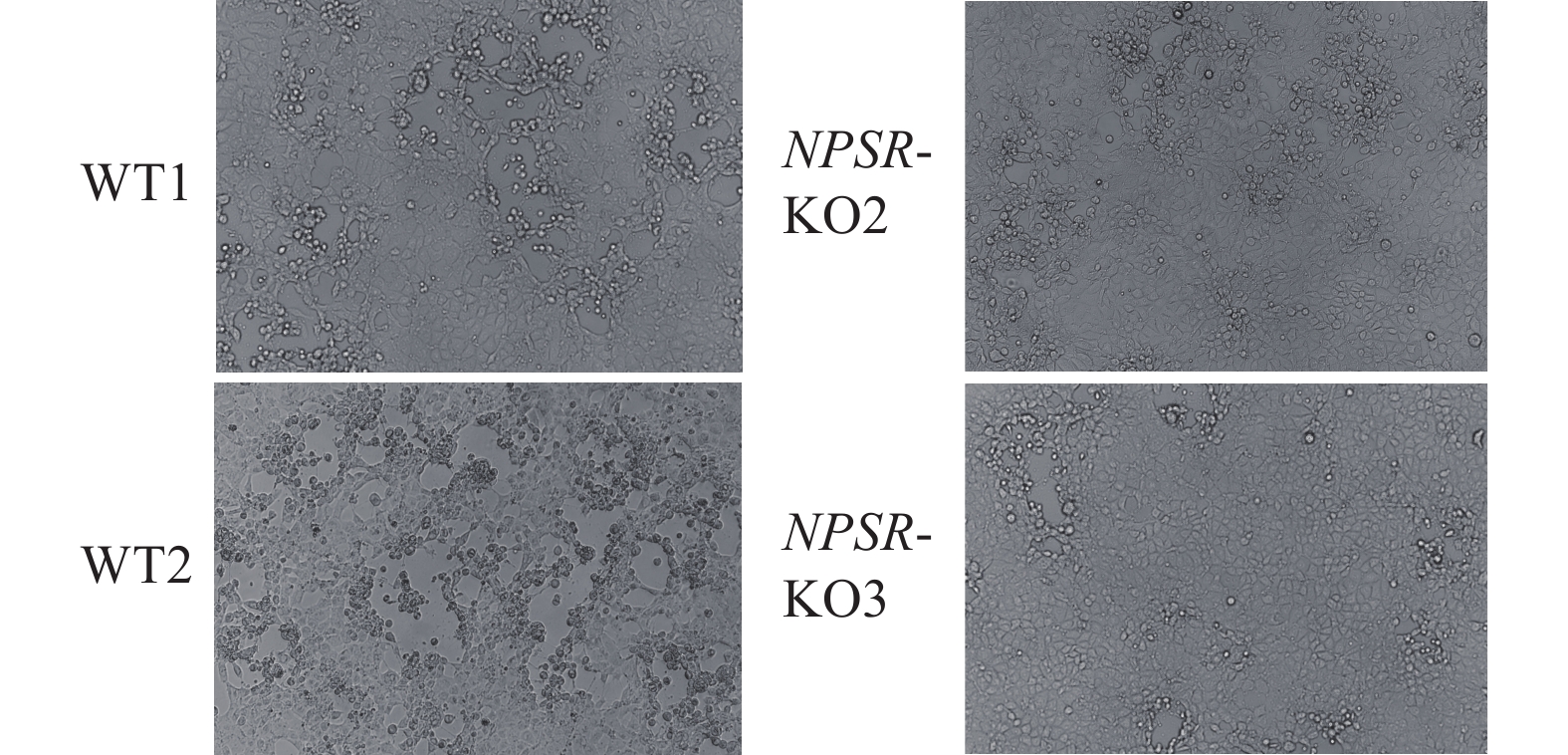

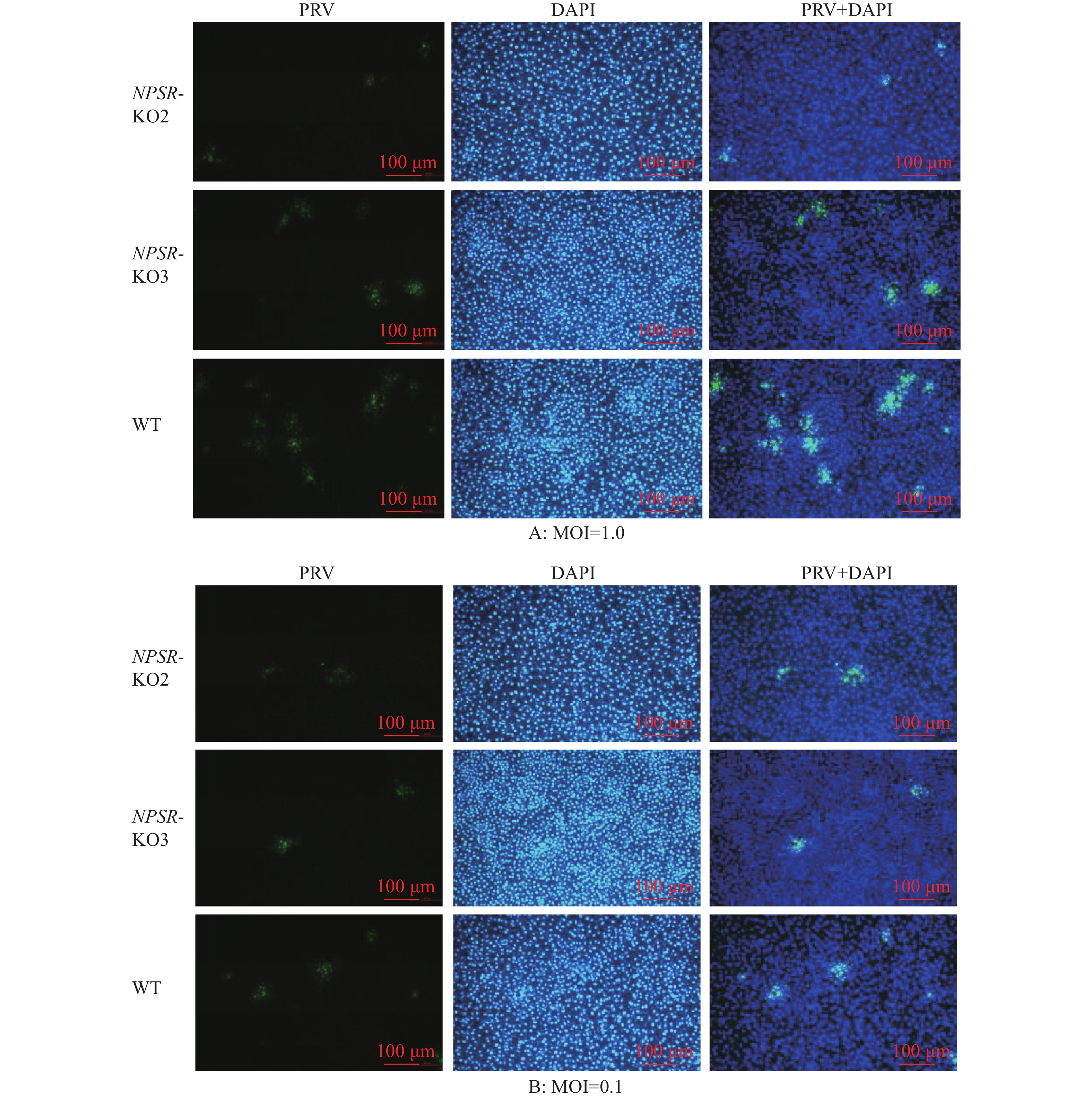

图 9 免疫荧光检测PRV对NPSR敲除细胞的感染能力

绿色荧光为PRV多克隆抗体阳性信号,蓝色DAPI染色为细胞核阳性信号,PRV+DAPI为ImageJ软件处理合成

Figure 9. Infectivity analysis of NPSR knockout cells with PRV infection by immunofluorescence

Green fluorescence is the positive signal of PRV polyclonal antibody, blue DAPI staining is the positive signal of cell nucleus, PRV+DAPI is synthesised by ImageJ software processing

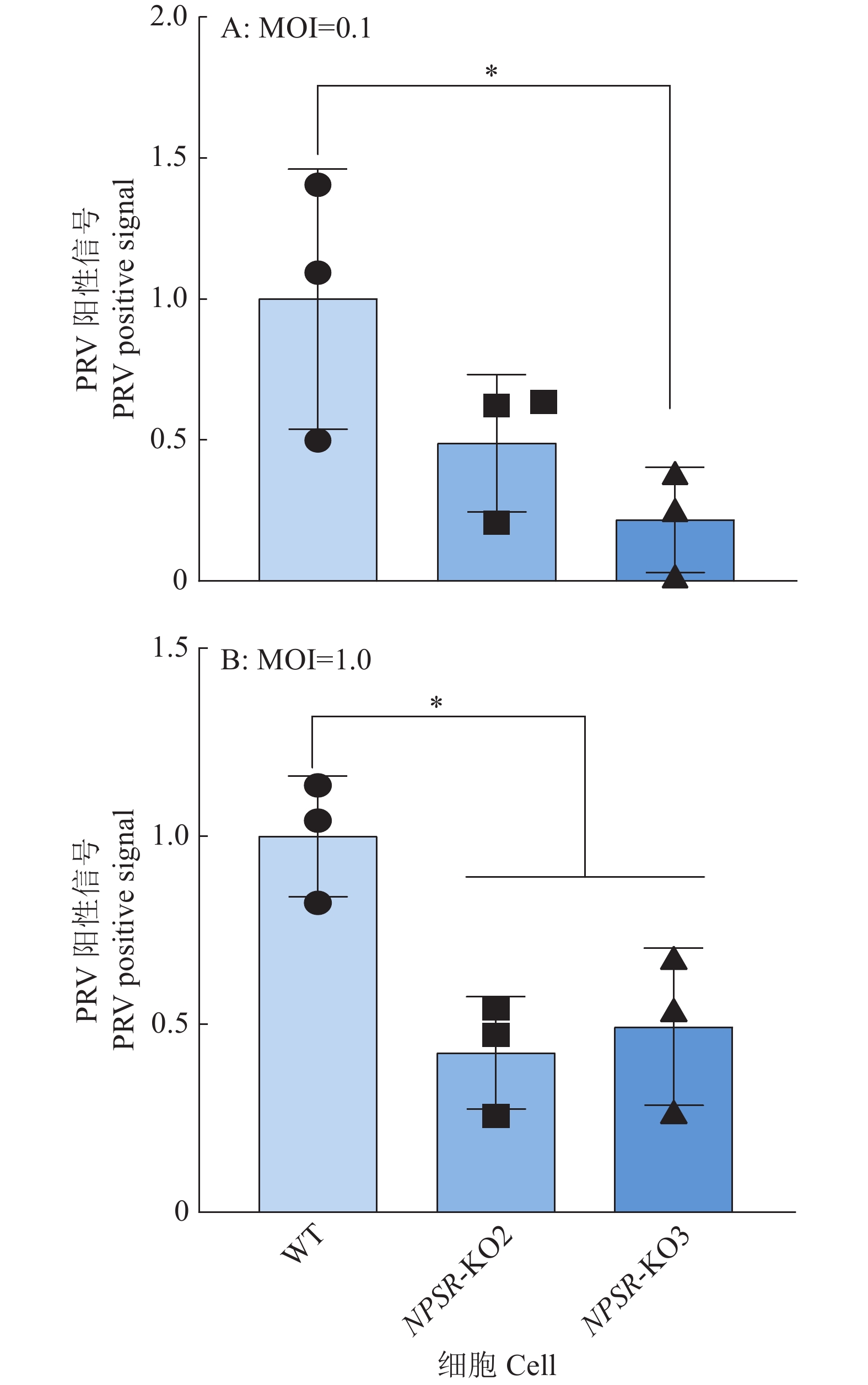

图 10 免疫荧光试验中PRV阳性感染细胞相对比例

通过ImageJ分析PRV阳性感染细胞比例,“*”表示在P < 0.05水平差异显著(t检验)

Figure 10. Relative proportion of PRV-positive infected cells in immunofluorescence experiments

The proportion of PRV-positive infected cells is analyzed by ImageJ, “*” indicates significant difference at P < 0.05 level (t test)

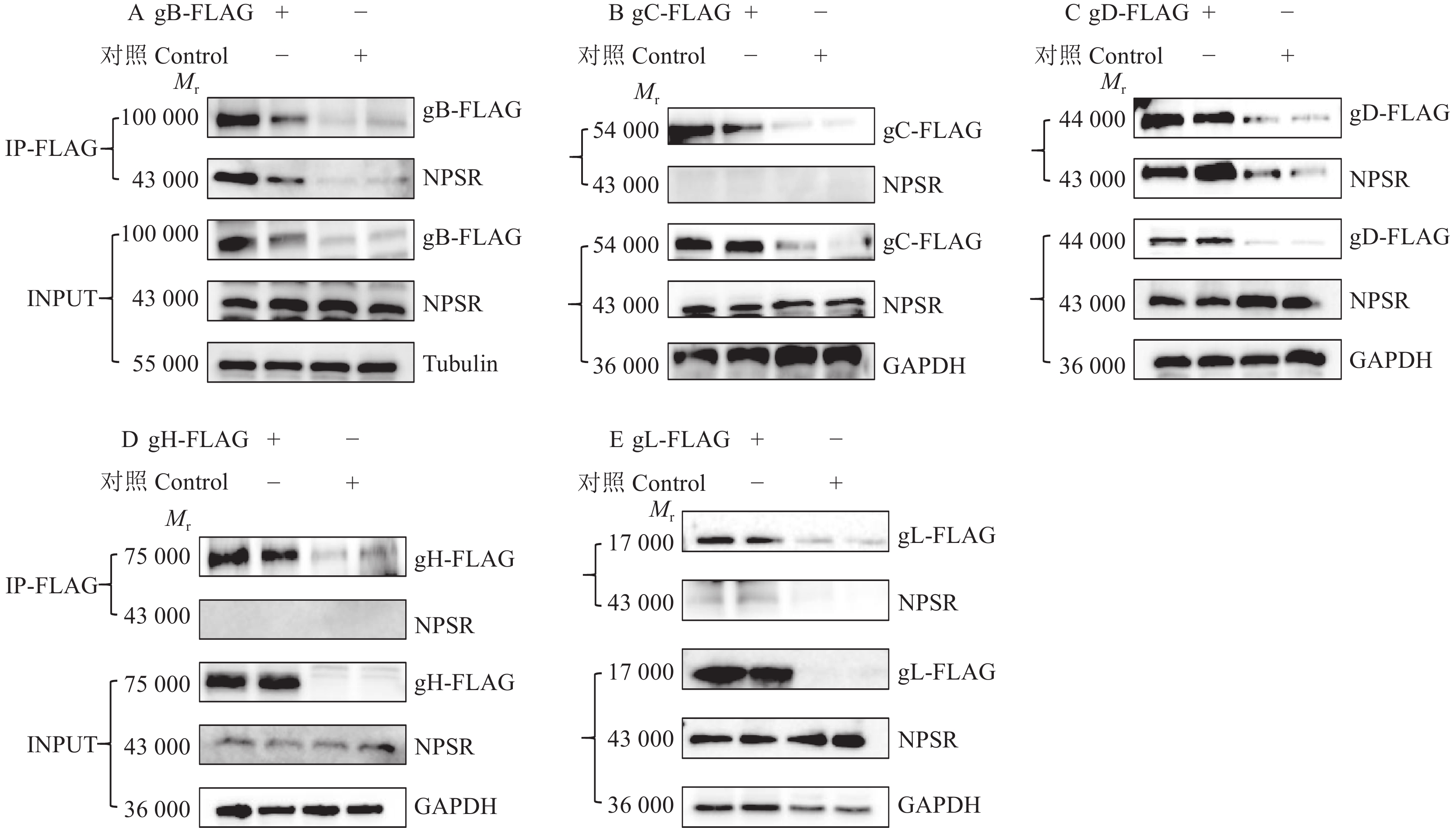

图 13 双质粒共转染证实NPSR通过与PRV表面糖蛋白相互作用影响病毒的感染

Mr表示相对分子质量,内参采用Tubulin或GAPDH蛋白

Figure 13. NPSR affects viral infection by interacting with PRV surface glycoproteins through co-transfection of NPSR- and PRV surface glycoprotein-expressing plasmids

Mr indicates relative molecular mass, the internal reference is Tubulin or GAPDH protein

表 1 引物信息

Table 1 Primer information

引物

Primer引物序列(5′→3′)

Primer sequenceNPSR-sgRNA GGTCATGTATGGCGTCCAGT NPS-sgRNA GGACAGCTGCCCAACTAGGA NPSR-F CCAAGTATGCTCCCAAAGGA NPSR-R TTGGGCTCAGCACACAGTAG NPS-F GTTTCAGCAAATCCCCCTTT NPS-R TGGTGTCAAACTTCTGCTGC FAM-PRV-gE CAGCGCGAGCCGCCCATCGTCAC PRV gE-F CCCACCGCCACAAAGAACACG PRV gE-R GATGGGCATCGGCGACTACCTG IL6-F AATCCAGACAAAGCCACCAC IL6-R TCCACTCGTTCTGTGACTGC IFNβ-F TGGAGGAAATCATGGAGGAG IFNβ-R ACTGTCCAGGCACAGCTTCT GAPDH-F CCACCCAGAAGACTGTGGAT GAPDH-R AAGCAGGGATGATGTTCTGG -

[1] POMERANZ L E, REYNOLDS A E, HENGARTNER C J. Molecular biology of pseudorabies virus: Impact on neurovirology and veterinary medicine[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2005, 69(3): 462-500. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.3.462-500.2005

[2] 王春芳, 付琦媛, 郑宾宾, 等. 伪狂犬病毒跨物种感染与传播[J]. 病毒学报, 2022, 38(4): 1001-1006. [3] BO Z, LI X. A review of pseudorabies virus variants: Genomics, vaccination, transmission, and zoonotic potential[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(5): 1003. doi: 10.3390/v14051003

[4] VERPOEST S, CAY B, FAVOREEL H, et al. Age-dependent differences in pseudorabies virus neuropathogenesis and associated cytokine expression[J]. Journal of Virology, 2017, 91(2): e02058-16.

[5] NARITA M, IMADA T, HARITANI M. Immunohistological demonstration of spread of Aujeszky’s disease virus via the olfactory pathway in HPCD pigs[J]. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 1991, 105(2): 141-145. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(08)80069-2

[6] ZHENG H H, FU P F, CHEN H Y, et al. Pseudorabies virus: From pathogenesis to prevention strategies[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(8): 1638. doi: 10.3390/v14081638

[7] NAUWYNCK H, GLORIEUX S, FAVOREEL H, et al. Cell biological and molecular characteristics of pseudorabies virus infections in cell cultures and in pigs with emphasis on the respiratory tract[J]. Veterinary Research, 2007, 38(2): 229-241. doi: 10.1051/vetres:200661

[8] CHEN J, LI G, WAN C, et al. A comparison of pseudorabies virus latency to other alpha-herpesvirinae subfamily members[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(7): 1386. doi: 10.3390/v14071386

[9] HUANG X, QIN S, WANG X, et al. Molecular epidemiological and genetic characterization of pseudorabies virus in Guangxi, China[J]. Archives of Virology, 2023, 168(12): 285. doi: 10.1007/s00705-023-05907-2

[10] LIU Q, KUANG Y, LI Y, et al. The epidemiology and variation in pseudorabies virus: A continuing challenge to pigs and humans[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(7): 1463. doi: 10.3390/v14071463

[11] LI X D, FU S H, CHEN L Y, et al. Detection of pseudorabies virus antibodies in human encephalitis cases[J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 2020, 33(6): 444-447.

[12] PENG Z, LIU Q, ZHANG Y, et al. Cytopathic and genomic characteristics of a human-originated pseudorabies virus[J]. Viruses, 2023, 15(1): 170. doi: 10.3390/v15010170

[13] YANG H, HAN H, WANG H, et al. A case of human viral encephalitis caused by pseudorabies virus infection in China[J]. Frontiers in Neurology, 2019, 10: 534. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00534

[14] LIU Q, WANG X, XIE C, et al. A novel human acute encephalitis caused by pseudorabies virus variant strain[J]. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2021, 73(11): E3690-E3700. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa987

[15] YE G, LIU H, ZHOU Q, et al. A tug of war: Pseudorabies virus and host antiviral innate immunity[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(3): 547. doi: 10.3390/v14030547

[16] SAPIR A, AVINOAM O, PODBILEWICZ B, et al. Viral and developmental cell fusion mechanisms: Conservation and divergence[J]. Developmental Cell, 2008, 14(1): 11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.008

[17] CONNOLLY S A, JARDETZKY T S, LONGNECKER R. The structural basis of herpesvirus entry[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2021, 19(2): 110-121. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00448-w

[18] TAN L, WANG K, BAI P, et al. Host cellular factors involved in pseudorabies virus attachment and entry: A mini review[J]. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2023, 10: 1314624. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1314624

[19] ZHANG N, YAN J, LU G, et al. Binding of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D to nectin-1 exploits host cell adhesion[J]. Nature Communications, 2011, 2: 577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1571

[20] PAN Y, GUO L, MIAO Q, et al. Association of THBS3 with glycoprotein D promotes pseudorabies virus attachment, fusion, and entry[J]. Journal of Virology, 2023, 97(2): e01871-22.

[21] GRUND T, NEUMANN I D. Neuropeptide S induces acute anxiolysis by phospholipase C-dependent signaling within the medial amygdala[J]. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2018, 43(5): 1156-1163. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.169

[22] GOTTSCHALK M G, DOMSCHKE K. Genetics of generalized anxiety disorder and related traits[J]. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2017, 19(2): 159-168. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.2/kdomschke

[23] XU Y L, REINSCHEID R K, HUITRON-RESENDIZ S, et al. Neuropeptide S: A neuropeptide promoting arousal and anxiolytic-like effects[J]. Neuron, 2004, 43(4): 487-497. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.005

[24] TAPMEIER T T, RAHMIOGLU N, LIN J, et al. Neuropeptide S receptor 1 is a nonhormonal treatment target in endometriosis[J]. Science Translational Medicine, 2021, 13(608): eabd6469. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd6469

[25] SMITH K L, PATTERSON M, DHILLO W S, et al. Neuropeptide S stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and inhibits food intake[J]. Endocrinology, 2006, 147(7): 3510-3518. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1280

[26] FANG C, ZHANG J, WAN Y, et al. Neuropeptide S (NPS) and its receptor (NPSR1) in chickens: Cloning, tissue expression, and functional analysis[J]. Poultry Science, 2021, 100(12): 101445. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101445

[27] ERDMANN F, KÜGLER S, BLAESSE P, et al. Neuronal expression of the human neuropeptide S receptor NPSR1 identifies NPS-induced calcium signaling pathways[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(2): e0117319.

[28] XU Y L, GALL C M, JACKSON V R, et al. Distribution of neuropeptide S receptor mRNA and neurochemical characteristics of neuropeptide S-expressing neurons in the rat brain[J]. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2007, 500(1): 84-102. doi: 10.1002/cne.21159

[29] LI C, MA Y, CAI Z, et al. Neuropeptide S and its receptor NPSR enhance the susceptibility of hosts to pseudorabies virus infection[J]. Research in Veterinary Science, 2022, 146: 15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.03.008

[30] D’AMATO M, BRUCE S, BRESSO F, et al. Neuropeptide S receptor 1 gene polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133(3): 808-817. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.012

[31] VENDELIN J, BRUCE S, HOLOPAINEN P, et al. Downstream target genes of the neuropeptide S-NPSR1 pathway[J]. Human Molecular Genetics, 2006, 15(19): 2923-2935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl234

[32] NEURATH M F, FINOTTO S. IL-6 signaling in autoimmunity, chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer[J]. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews, 2011, 22(2): 83-89.

[33] XU J J, CHENG X F, WU J Q, et al. Pseudorabies virus pUL16 assists the nuclear import of VP26 through protein-protein interaction[J]. Veterinary Microbiology, 2021, 257: 109080. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109080

[34] VALLBRACHT M, REHWALDT S, KLUPP B G, et al. Functional relevance of the N-terminal domain of pseudorabies virus envelope glycoprotein H and its interaction with glycoprotein L[J]. Journal of Virology, 2017, 91(9): e00061.

[35] WU H, QI H, WANG B, et al. The mutations on the envelope glycoprotein D contribute to the enhanced neurotropism of the pseudorabies virus variant[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2023, 299(11): 105347. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105347

下载:

下载: