Research progress of epigenetic mechanism of noncoding RNAs regulating avian skeletal muscle development

-

摘要:

肉、蛋、奶是畜牧业最主要的三大产品,其中,肉的需求量是最高的。肌肉是动物躯体的重要组成部分,仅骨骼肌就已占全身体质量的40%左右。骨骼肌在调节动物新陈代谢、机体运动、能量储存和健康等方面至关重要,是机体功能正常运转的必要组分。骨骼肌发育过程极其复杂,主要包括体节细胞增殖分化、成肌细胞增殖分化、肌管成熟以及肌纤维形成等环节,整个过程受许多遗传因子调控,其中,由微小RNAs(miRNAs)、长链非编码RNAs(lncRNAs)、环状RNAs(circRNAs)等几种类型构成的非编码RNAs(ncRNAs)可以通过靶向关键因子调控骨骼肌发育过程。本文介绍了各类ncRNAs的特征与功能,总结了近年来有关ncRNAs在家禽肌肉生长发育中的研究,阐述ncRNAs在骨骼肌生长发育进程中的表观遗传调控机制,为改善家禽生长发育提供参考。

Abstract:Meat, eggs and milk are three important products in animal husbandry, among which, the demand for meat is the highest. Muscle is an essential component of animal body, and skeletal muscle accounts for about 40% of body weight. Skeletal muscle plays an important role in animal metabolism, body movement, energy storage and health, and it's the essential part in body function normal running. The development process of skeletal muscle is extremely complex, mainly including somite proliferation and differentiation, myoblast proliferation and differentiation, myotube fusion, and the formation of muscle fiber, and the whole progress is regulated by many genetic factors. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which mainly consist of micro RNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), can regulate skeletal muscle development by targeting key factors. This paper briefly described the characteristics and functions of those ncRNAs, then reviewed recent studies of ncRNAs in avian muscle growth and development, and elucidated the epigenetic regulatory mechanism of ncRNAs in skeletal muscle growth and development, which could provide references for improving avian growth and development.

-

Keywords:

- noncoding RNA /

- skeletal muscle /

- growth and development /

- epigenetic regulation

-

禾谷孢囊线虫Heterodera avenae是重要的病原线虫,其寄主包括小麦属、大麦属等32个属60余种禾本科作物和紫羊茅等多种杂草,严重影响小麦、燕麦、大麦、裸大麦等作物生产[1]。禾谷孢囊线虫病在全球多个国家均有发生和为害[2],一般患病麦田可减产20%~30%[3],严重时可使小麦减产50%~90%[4]。1989年,该病在我国湖北首次被公开报道,随后在北京、河南、河北、山西、陕西、内蒙古、甘肃等地相继被发现[1, 5-8]。侵染麦类的孢囊线虫有禾谷孢囊线虫H. avenue、菲利普孢囊线虫H. filipjevi、麦类孢囊线虫H. latipons、双膜孔孢囊线虫H. bifenestra和稀少孢囊线虫H. mani等。目前,我国报道的种主要为H. avenae和H. filipjevi[9]。作为我国小麦种植大省,甘肃省小麦常年种植面积超过90万hm2,受到禾谷孢囊线虫的严重侵害。李惠霞等[10]调查结果显示,甘肃省禾谷孢囊检出率超过47.9%,2/3以上的乡镇有孢囊线虫分布,全省约44.2万hm2小麦受禾谷孢囊线虫病为害。

禾谷孢囊线虫病主要通过土壤传播,可通过农事操作、农业机械、人、畜、水流等途径近距离传播,也可经暴雨、洪水、运输车辆等途径远距离传播[11-12]。由于线虫及其寄主地理分布非常广泛,寄主种类繁多,易于传播扩散,化学防治存在成本高、毒性大、易残留、破坏土壤生态、污染水源、线虫易产生抗药性等一系列弊端,生物防治因以下优点而备受关注,选择性强、对人及家畜无毒无害;利用可再生资源,低碳环保;对环境友好,对生态环境影响较小,易被植物、土壤微生物和阳光降解[13]。

在线虫病害生物防治方面研究较多的有厚垣普可尼亚菌Pochonia chlamydosporia、少孢节丛孢Arthrobotrys oligospora[14]、球孢白僵菌Beauveria bassiana[15]和淡紫紫孢菌Purpureocillium lilacinum[16]等真菌,其中淡紫紫孢菌和厚垣普可尼亚菌已经商品化,并广泛使用[17-18]。目前,用于植物线虫的生防细菌有苏云金芽孢杆菌Bacillus thuringiensis[19]、坚强芽孢杆菌Bacillus firmus[20]和枯草芽孢杆菌Bacillus subtilis[21]等。为了进一步拓展禾谷孢囊线虫病的生防菌资源,本研究拟对前期筛选得到的2株真菌的杀线虫活性进行离体活性测定和盆栽试验,以期为禾谷孢囊线虫病生防菌的利用提供理论依据。

1. 材料与方法

1.1 材料

禾谷孢囊线虫采自甘肃省永登县受禾谷孢囊线虫侵染的麦田。

供试菌株A1和B1由甘肃农业大学植物线虫学实验室前期分离和保存。

1.2 方法

1.2.1 形态学鉴定

挑取待测真菌菌丝于PDA培养基上,在25 ℃条件下培养7 d后,观察菌株生长速度、菌落颜色及表面特征等,在显微镜下观察菌丝、孢子,记录菌株的形态特征。

1.2.2 分子生物学鉴定

按照生工真菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒说明书提取真菌基因组DNA,−20 ℃保存备用。采用通用引物ITS1(5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGGAAGTAA-3′)和ITS4(5′-TCCTCCUCTTATTUATATUC-3′)进行PCR扩增。扩增产物送上海生物工程有限公司测序,在NCBI数据库上通过BLAST比对分析,用MEGA 6.0中的UPGAM法构建系统发育树。

1.2.3 禾谷孢囊线虫的采集

选择甘肃省永登县禾谷孢囊线虫发生较严重的田地,用Z字形取样法采集土样,去除表层干土,取0~20 cm层的土壤,将多点土样混合后装入封口塑料袋中,带回实验室。用漂浮法分离孢囊,在解剖镜下观察,挑取饱满的棕色孢囊,于4 ℃冰箱保存备用。

1.2.4 卵和2龄幼虫悬浮液的制备

挑取饱满的棕色孢囊,加入5 g·L−1 NaClO溶液,表面消毒3 min,灭菌水多次清洗后,用橡皮塞磨破孢囊后,将卵悬浮液倒入200目和500目组合筛,用无菌水冲洗,收集卵悬浮液,将卵悬浮液浓度调整为1 000 mL−1。

4 ℃冰箱处理6~8周的禾谷孢囊线虫,用5 g·L−1 NaClO溶液表面消毒3 min,灭菌水清洗3~5次后,置于100目网筛上。将网筛置于灭菌培养皿里,加灭菌水至浸没孢囊,15 ℃黑暗条件下孵化。4 d后开始收集2龄幼虫,并配置成浓度为1 000 mL−1的线虫悬浮液。

1.2.5 真菌孢子悬浮液的制备

取在PDA平板上培养7 d的菌株,加入1滴吐温80和2.5 mL无菌水冲洗,使其分生孢子脱落,得到分生孢子悬浮液,用血球计数板计数,调整浓度为1×107 CFU·mL−1备用。

1.2.6 发酵液的制备

将2 mL 1×107 CFU·mL−1的分生孢子悬浮液接种在100 mL PD培养液中(150 mL三角瓶),26 ℃,150 r·min−1振荡培养120 h。10 000 r·min−1 10 min,用0.22 μm细菌过滤器过滤。经上述处理后的悬浮液作为发酵原液,同时用灭菌水制备5倍和10倍发酵液,并测定发酵液的pH。

1.2.7 生防菌对禾谷孢囊线虫孢囊的寄生作用

将分离出的生防菌株转移至PDA培养基上,等菌落直径长至培养皿1/2时,将消毒后的孢囊放入菌落边缘,每皿10个孢囊。培养7 d后,将孢囊移出培养皿,5 g·L−1 NaClO溶液表面消毒3 min,每个孢囊单独置于经灭菌的滤纸片上,加灭菌水保湿培养,6 d后观察菌株对孢囊的寄生作用。

1.2.8 真菌发酵液对卵孵化的影响

分别吸取100 μL生防菌原液(1倍)、5倍、10倍发酵液,加入到灭菌的96孔细胞培养板中,然后向每个孔中分别加入200 μL卵悬浮液。每个浓度重复3次,以空白培养基滤液为对照。试验在15 ℃条件下,每隔2 d在显微镜下观察1次。12 d后镜检、记录各菌株发酵液对卵孵化的影响,统计相对抑制率。

$$ \begin{array}{l} {\text{相对抑制率}} = ( {{\text{对照的线虫数量}}} - {{\text{处理的线虫数量}}} )/ \\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;{\text{对照的线虫数量}} \times 100{\text{%}}{ \text{。}} \end{array} $$ 1.2.9 真菌发酵液对J2的致死作用

分别吸取100 μL生防菌1倍、5倍、10倍发酵液,加入无菌96孔细胞培养板中,每个浓度重复3次,然后向每个孔中分别加入200 μL 2龄幼虫悬浮液。试验在15 ℃条件下进行,以培养基滤液为空白对照,每个处理重复3次。分别在24、48和72 h镜检各处理中线虫的死亡情况,用NaOH法测定线虫的死活,并计算死亡率和校正死亡率。

$$\text{线虫死亡率} = {\text{死亡线虫数}}/{\text{供试线虫数}} \times 100{\text{%}} \text{,}$$ $$ \begin{array}{l} \text{校正死亡率} = ({{\text{处理线虫死亡率} -}}{{\text{对照线虫死亡率}}})/ \\ \quad\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; ({{1 - \text{对照死亡率}}}) \times 100{\text{%}} \text{。} \end{array} $$ 1.2.10 室内防效测定

从禾谷孢囊线虫病田采集土样,过筛使每100 g土含20个孢囊,然后将病土装入直径21 cm的花盆,每盆约1 500 g土。

制备麦麸培养基,高温灭菌(121 ℃,30 min),接菌后28 ℃条件下培养7 d。以1%、2%和3%的比例将其与病土混匀,装入盆中,挑选饱满的宁春50号种子播种,每盆13粒,每处理4盆,以不接生防真菌的病土为对照。

播种10 d后调查出苗率,90 d后调查发病情况,将植株从盆中取出,尽可能保持根系完整。将植株根系用自来水冲洗干净,放在盛有清水的塑料盘中调查病情,记录土中孢囊量,计算孢囊减少率,并测量小麦的根长和株高。

$$ \begin{array}{l} \text{孢囊减少率} = ({{\text{对照孢囊数量} -}} {{\text{处理孢囊数量}}})/\\ \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;{\text{对照孢囊数量}} \times 100{\text{%}} \text{。} \end{array} $$ 1.3 数据处理

用Excel 2003进行数据处理和表格绘制,并采用 SPSS 19.0软件进行统计分析,用最小显著差异法进行多重比较。

2. 结果与分析

2.1 菌株的形态学鉴定

A1菌株在PDA培养基25 ℃条件下培养7 d,菌落直径为3.2~4.5 cm,菌落中央淡黄色至深绿色,边缘白色,有放射状沟纹(图1a)。菌落背面奶油色至淡褐色(图1b),产生大量分生孢子。分生孢子球形或近球形,长4.0~6.5 μm,宽4.5~6.0 μm ,一部分菌丝形成长而粗糙的分生孢子梗,顶端产生烧瓶形顶囊,表面着生许多小梗,小梗上产生成串的分生孢子(图1c)。初步鉴定为曲霉属Aspergillus真菌(注:A1的鉴定已发表于大豆科学)。

B1菌株在PDA 培养基上,菌落初期白色呈毡状,后期变为浅绿色,致密地平铺在培养基平板上(图1d),背面黄绿色或金黄色(图1e),孢子聚生成头状。瓶梗细胞单生或2~5个轮生。分生孢子椭球形,长2.0~4.0 μm,宽2.5~3.8 μm,壁光滑(图1f),初步鉴定为木霉属Trichoderma真菌。

2.2 菌株的分子学鉴定

菌株A1和B1的ITS片段长度分别为594和652 bp,GenBank登录号分别为MH 937578.1和MH 937579.1。序列经BLAST比对分析,用MEGA 6.0中的UPGMA法构建系统发育树,由图2a可知,在亲缘关系上,A1与登录号为JF 412785.1、HQ 340102.1、AY 373859.1、MG 662404.1的寄生曲霉聚为一支,序列相似性为99%,故将其鉴定为寄生曲霉Aspergillus parasiticus。由图2b可知,在亲缘关系上,B1与登录号为KU 375460.1的长枝木霉亲缘关系最近,序列相似性为99%,故将其鉴定为长枝木霉Trichoderma longilbrachiatum。

2.3 生防菌对孢囊的寄生作用

从图3可以看出,菌株A1和B1对禾谷孢囊的寄生率随侵染时间的增加呈直线上升趋势。在处理后第6天,菌株A1和B1的寄生率均在24.00%以上。在处理后第10天,菌株A1和B1的寄生率均在45.00%以上。菌株A1和B1寄生率上升幅度相近,均在第14天达到80.00%以上,寄生率分别是90.00%和83.33%。菌株A1在6~14 d,寄生率均略高于B1。

2.4 生防菌发酵液对线虫卵孵化的抑制作用

A1、B1真菌1倍、5倍、10倍稀释发酵液对卵孵化抑制作用测定结果表明,A1和B1各稀释倍数发酵液对卵孵化抑制率均在45.00% 以上。随着发酵液稀释倍数增加,J2孵化数量呈逐渐增加的趋势。从图4可知,发酵液浓度对卵孵化有显著影响(P<0.01,F=9.71)。发酵液处理12 d 后,A1的 1倍发酵液对卵孵化的抑制率为63.98%,1倍和5倍稀释液对卵的抑制率差异不显著(P>0.05),但均显著高于10倍(P<0.05)(图4a)。B1的1倍发酵液对卵孵化的抑制率为67.56%,且显著高于5倍、10倍稀释液(P<0.05)(图4b)。

2.5 生防菌发酵液对J2的致死作用

随着A1、B1真菌发酵液稀释倍数的增加,2龄幼虫的死亡率总体呈减小的趋势。随着处理时间的延长,同一浓度发酵液的校正死亡率呈显著增强趋势,具体结果见表1。

表 1 真菌发酵液对禾谷孢囊线虫2龄幼虫的致死作用Table 1. Lethal effects of fungal fermentation broth on the second-stage juveniles of cereal cyst nematode菌株

Straint/h 最终稀释倍数

Final dilution ratio线虫死亡数量1)

Number of dead nematode死亡率/%

Mortality rate校正死亡率1)/%

Corrected mortality rateA1 24 1× 79.33±2.33a 39.67 39.36±1.17a 5× 40.67±9.68b 20.33 19.93±4.87b 10× 34.67±1.67b 17.33 16.92±0.84b CK 1.00±0.58c 0.50 48 1× 107.33±4.91a 53.67 51.52±2.46a 5× 49.33±8.57b 24.67 22.43±4.30b 10× 37.33±1.86b 18.67 16.42±0.93b CK 4.67±0.88c 2.30 72 1× 138.00±5.51a 69.00 68.14±2.83a 5× 53.00±11.68b 26.50 24.46±0.06b 10× 39.67±1.45b 19.83 17.61±0.75b CK 5.33±0.88c 2.70 B1 24 1× 95.00±3.21a 47.50 47.24±1.62a 5× 87.00±9.17a 43.50 43.22±4.61a 10× 70.67±7.69a 35.33 35.01±3.86 CK 1.00±0.58b 0.50 48 1× 125.00±4.51a 62.50 60.38±2.26a 5× 105.67±12.99ab 52.83 50.69±6.52a 10× 79.00±8.14b 39.50 37.31±4.09b CK 4.67±0.88c 2.30 72 1× 186.33±4.33a 93.17 92.98±2.23a 5× 105.67±12.57b 52.83 51.52±6.46b 10× 84.67±4.33b 42.33 40.73±2.23b CK 5.33±0.88c 2.70 1)表中数据为平均数±标准误,相同菌株相同时间同列数据后不同小写字母表示差异显著(P<0.05,LSD法)

1)Datas in the table are means±SE, different lowercase letters in the same column of the same strain at the same time indicate significant difference (P<0.05, LSD method)经菌株A1和B1的发酵液处理后,死亡线虫数显著多于对照组(P<0.05),说明这3种发酵液均对线虫有致死作用。菌株A1发酵液处理24、48、72 h后线虫校正死亡率为16.00%以上,A1的1倍稀释液在72 h对2龄幼虫的校正死亡率较高为68.14%。菌株B1发酵液处理24 、48 、72 h后线虫校正死亡率为35.00%以上,B1的1倍稀释液在72 h对2龄幼虫的校正死亡率最高为92.98%,显著高于5倍、10倍(P<0.05)。在相同处理时间和发酵液稀释倍数下,菌株B1校正死亡率均大幅高于菌株A1。

2.6 生防菌菌肥室内防治禾谷孢囊线虫的效果

室内盆栽试验表明,随着生防菌菌肥量的增大,孢囊减少率持续增多。由表2可知,A1的3%菌肥处理后,孢囊减少率为31.71%,显著高于1%和2%菌肥处理(P<0.05)。小麦根长增加28.82%,株高增加20.38%。B1的3%菌肥处理后,孢囊减少率36.04%,显著高于1%和2%菌肥处理(P<0.05)。小麦根长增加59.62%,株高增加21.43%。

表 2 真菌对禾谷孢囊线虫病室内防治效果测定Table 2. Control efficiencies of the fungi on cereal cyst nematode in indoor pots菌株

Strain处理1)

Treatment根长2)/cm

Root length根长增长率/%

Increased percentage of root length株高2)/cm

Plant height株高增长率/%

Increased percentage of plant hight孢囊减少率2)/%

Cyst reduction rateA1 1% 11.35±0.32b 2.53 34.43±1.25a 11.79 4.88±1.69c 2% 13.08±0.50ab 18.16 36.50±1.27a 18.51 11.65±0.97b 3% 14.26±0.60a 28.82 37.23±1.31a 20.38 31.71±1.69a CK 11.07±1.05b 30.80±1.14b B1 1% 15.67±0.67a 41.55 30.62±0.59b −0.58 7.25±2.55b 2% 15.40±1.81a 39.11 35.39±0.34a 14.90 12.19±1.24b 3% 17.67±0.76a 59.62 37.40±1.29a 21.43 36.04±0.72a CK 11.07±1.05b 30.80±1.14b 1) 处理为生防菌菌肥与病土质量比;2) 该列数据为平均数±标准误,相同菌株同列数据后不同小写字母表示差异显著(P<0.05,LSD法)

1) The mass ratio of fungus fertilizer to soil; 2) Datas in this column are means ± SE, different lowercase letters in the same column of the same strain indicate significant difference (P<0.05, LSD method)3. 讨论与结论

寄生曲霉属于半知菌亚门丝孢菌纲丝孢目从梗孢科[22],其广泛存在于土壤、灰尘和植物上。目前研究集中于寄生曲霉的种类鉴定和对甘蔗绵蚜、吹绵蚧等害虫的生物防治方面[23-25],鲜见寄生曲霉对其他植物寄生线虫有生防作用的报道。长枝木霉生长速度快、产孢量大、对植物病原菌有一定的拮抗作用,可作为农业上重要的生防菌株[25],目前研究集中于其对南方根结线虫的防治及其根际定殖作用[26]、对禾谷孢囊线虫的寄生和致死作用[27],但长枝木霉对禾谷孢囊线虫的盆栽防效试验的报道甚少。

生物农药源于自然,具有作用谱广、对生态环境影响小、对人畜低毒等特点[28-29],筛选细菌、真菌等微生物来防治植物病原线虫,对生态环境保护具有重要的意义。本研究筛选的具有杀线虫活性的菌株A1和B1,经鉴定分别为寄生曲霉Aspergillus parasiticus和长枝木霉 Trichoderma longibrachiatum,均对禾谷孢囊具有良好的寄生性,分别在第6天、第10天后,寄生率超过50.00%,侵染2周左右禾谷孢囊寄生率达80.00%以上,这与迟君道等[30]报道的结果基本一致。

卵孵化试验中,随着菌株A1和B1发酵液稀释浓度的增大,这2株菌的卵孵化率相应增大。菌株A1和B1的1倍稀释液pH分别为4.27和5.72,菌株A1和B1的1倍稀释液抑制卵孵化效果均好于5倍和10倍稀释液。这可能与发酵液pH有关,pH可影响发酵液中杀线虫物质的活性,还可以直接影响卵的孵化[31]。

菌株A1和B1不同浓度发酵液对禾谷孢囊线虫2龄幼虫具有一定的毒杀作用,随着菌株发酵液浓度的升高,2龄幼虫死亡率也相应增高,并且随着处理时间的延长呈上升趋势。该结果和梁晨等[32]报道的研究结果基本一致。发酵液对线虫作用的效果与杀线虫活性物质成分的浓度和线虫裸露程度有关,呈现出浓度越低、线虫死亡率越低的规律[33]。赵迪[34]发现菌株 Snef 5的杀线虫活性物质是一种强极性、弱酸性的水溶性抗生素。李玲玉等[35]发现放线菌Snea253代谢产物中氨基糖类物质对线虫有毒性。Niu 等[36]从细菌 Bacillus nematocidal中分离纯化出对线虫有毒性作用的丝氨酸蛋白酶,能够很大程度上破坏线虫表皮并水解胶原蛋白和凝胶,从而使线虫死亡。刘霆等[37]研究发现,真菌Snf 907代谢物,在原液、5×、10×、20×稀释浓度下,对大豆孢囊线虫2龄幼虫的校正死亡率分别是 96.33%、83.18%、63.15%和47.04%,这与本试验结果A1和B1在发酵液原液处理下,对2龄幼虫最高的校正死亡率分别为68.14%和92.98% 相比存在差异。这可能与菌株种类、产生的活性物质类型、作用对象、对线虫的作用机理有关[37]。各类真菌的代谢产物不同,杀线虫的活性物质也不相同,不同的孢囊线虫寄生真菌有其独特作用机理[38]。

盆栽试验结果表明,菌株A1、B1的生物菌肥均能显著减少土壤中的禾谷孢囊线虫的孢囊数量,对小麦植株根长和株高有不同程度的影响。2种菌肥可使小麦株高增加、根长增长。适量菌肥处理可显著促进小麦根的生长,与对照相比,2种真菌3%(w)处理组小麦根长均增加3 cm以上。除B1 1%(w)菌肥处理除外,不同浓度的2种菌肥均有效促进了小麦株高增加,这与Zhang等[20]的研究结果一致,但本试验中2株生防菌3%(w)菌肥处理后的孢囊减少率低于其6%(w)的菌剂处理,可能是由于生物菌肥中加入的生物菌种和剂量不同所致。

本研究表明菌株A1和B1在防治禾谷孢囊线虫上有较好的应用前景,且B1的生防效果略优于A1。对于这2株生防菌的杀线虫活性物质成分、对线虫的作用机理等有待进一步深入的研究。

-

-

[1] 杨宁. 家禽业的核心将是保持高效优势[J]. 北方牧业, 2018(15): 7. [2] GÜLLER I, RUSSELL A P. MicroRNAs in skeletal muscle: Their role and regulation in development, disease and function[J]. J Physiol, 2010, 588(21): 4075-4087.

[3] PEARSON A M. Muscle growth and exercise[J]. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 1990, 29(3): 167-196. doi: 10.1080/10408399009527522

[4] FENG Y, CAO J H, LI X Y, et al. Inhibition of miR-214 expression represses proliferation and differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts[J]. Cell Biochem Funct, 2011, 29(5): 378-383. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1760

[5] SCHIAFFINO S, SANDRI M, MURGIA M. Activity-dependent signaling pathways controlling muscle diversity and plasticity[J]. Physiology (Bethesda), 2007, 22: 269-278.

[6] ZANOU N, GAILLY P. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and regeneration: Interplay between the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs) and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) pathways[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2013, 70(21): 4117-4130. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1330-4

[7] RULLMAN E, FERNANDEZ-GONZALO R, MEKJAVIĆ I B, et al. MEF2 as upstream regulator of the transcriptome signature in human skeletal muscle during unloading[J]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2018, 315(4): R799-R809. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00452.2017

[8] BRAUN T, GAUTEL M. Transcriptional mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle differentiation, growth and homeostasis[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2011, 12(6): 349-361. doi: 10.1038/nrm3118

[9] PERRY R L S, RUDNICK M A. Molecular mechanisms regulating myogenic determination and differentiation[J]. Front Biosci, 2000, 5: D750-D767. doi: 10.2741/A548

[10] GAO P F, GUO X H, DU M, et al. LncRNA profiling of skeletal muscles in Large White pigs and Mashen pigs during development[J]. J Anim Sci, 2017, 95(10): 4239-4250. doi: 10.2527/jas2016.1297

[11] CAO Y, YOU S, YAO Y, et al. Expression profiles of circular RNAs in sheep skeletal muscle[J]. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci, 2018, 31(10): 1550-1557. doi: 10.5713/ajas.17.0563

[12] SHI L, ZHOU B, LI P, et al. MicroRNA-128 targets myostatin at coding domain sequence to regulate myoblasts in skeletal muscle development[J]. Cell Signal, 2015, 27(9): 1895-1904. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.05.001

[13] DINGER M E, PANG K C, MERCER T R, et al. Differentiating protein-coding and noncoding RNA: Challenges and ambiguities[J]. PloS Comput Biol, 2008, 4(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000176.

[14] CESANA M, CACCHIARELLI D, LEGNINI I, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA[J]. Cell, 2011, 147(2): 358-369. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028

[15] OUYANG H, CHEN X, WANG Z, et al. Circular RNAs are abundant and dynamically expressed during embryonic muscle development in chickens[J]. DNA Res, 2018, 25(1): 71-86. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsx039

[16] BALLARINO M, MORLANDO M, FATICA A, et al. Non-coding RNAs in muscle differentiation and musculoskeletal disease[J]. J Clin Invest, 2016, 126(6): 2021-2030. doi: 10.1172/JCI84419

[17] HAYES J, PERUZZI P P, LAWLER S. MicroRNAs in cancer: Biomarkers, functions and therapy[J]. Trends Mol Med, 2014, 20(8): 460-469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.06.005

[18] LUO W, NIE Q, ZHANG X. MicroRNAs involved in skeletal muscle differentiation[J]. J Genet Genomics, 2013, 40(3): 107-116. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.02.002

[19] SAUNDERS M A, LIANG H, LI W H. Human polymorphism at microRNAs and microRNA target sites[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2007, 104(9): 3300-3305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611347104

[20] LAI E C. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation[J]. Nat Genet, 2002, 30(4): 363-364. doi: 10.1038/ng865

[21] SEOK H, HAM J, JANG E S, et al. MicroRNA target recognition: Insights from transcriptome-wide non-canonical interactions[J]. Mol Cells, 2016, 39(5): 375-381. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.0013

[22] LIU G, ZHANG R, XU J, et al. Functional conservation of both CDS- and 3′-UTR-located MicroRNA binding sites between species[J]. Mol Biol Evol, 2015, 32(3): 623-628.

[23] KREK A, GRÜN D, POY M N, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions[J]. Nat Genet, 2005, 37(5): 495-500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536

[24] GIRAL H, KRATZER A, LANDMESSER U. MicroRNAs in lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2016, 30(5): 665-676. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2016.11.010

[25] GROSS N, KROPP J, KHATIB H. MicroRNA signaling in embryo development[J]. Biology, 2017, 6(3). doi: 10.3390/biology6030034.

[26] 贾新正. 快慢型肉鸡miRNA的表达谱分析[D]. 广州: 华南农业大学, 2010. [27] WANG X G, YU J F, ZHANG Y, et al. Identification and characterization of microRNA from chicken adipose tissue and skeletal muscle[J]. Poult Sci, 2012, 91(1): 139-149. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01656

[28] LIN S, LI H, MU H, et al. Let-7b regulates the expression of the growth hormone receptor gene in deletion-type dwarf chickens[J]. BMC Genomics, 2012, 13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-306.

[29] WANG X G, SHAO F, GONG D Q, et al. miR-133a targets BIRC5 to regulate its gene expression in chicken[J]. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2013, 46(7): 1441-1447.

[30] OUYANG H, HE X, LI G, et al. Deep sequencing analysis of miRNA expression in breast muscle of fast-growing and slow-growing broilers[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2015, 16(7): 16242-16262. doi: 10.3390/ijms160716242

[31] LUO W, WU H, YE Y, et al. The transient expression of miR-203 and its inhibiting effects on skeletal muscle cell proliferation and differentiation[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2014, 5. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.289.

[32] WANG Z, OUYANG H, CHEN X, et al. Gga-miR-205a affecting myoblast proliferation and differentiation by targeting CDH11[J]. Front Genet, 2018, 9. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00414.

[33] TOWNLEY-TILSON W H D, CALLIS T E, WANG D Z. MicroRNAs 1, 133, and 206: Critical factors of skeletal and cardiac muscle development, function, and disease[J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2010, 42(8): 1252-1255. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.002

[34] JIA X, LIN H, ABDALLA B A, et al. Characterization of miR-206 promoter and its association with birthweight in chicken[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17(4). doi: 10.3390/ijms17040559

[35] LI G, LUO W, ABDALLA B A, et al. miRNA-223 upregulated by MYOD inhibits myoblast proliferation by repressing IGF2 and facilitates myoblast differentiation by inhibiting ZEB1[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2017, 8. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.479.

[36] GUO L, HUANG W, CHEN B, et al. Gga-mir-133a-3p regulates myoblasts proliferation and differentiation by targeting PRRX1[J]. Front Genet, 2018, 9. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00577.

[37] WANG Z, ZHANG X, LI Z, et al. MiR-34b-5p mediates the proliferation and differentiation of myoblasts by targeting IGFBP2[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(4). doi: org/10.3390/cells8040360.

[38] WANG J, HELIN K, JIN P, et al. Inhibition of in vitro myogenic differentiation by cellular transcription factor E2F1[J]. Cell Growth Differ, 1995, 6(10): 1299-1306.

[39] LUO W, LI G, YI Z, et al. E2F1-miR-20a-5p/20b-5p auto-regulatory feedback loop involved in myoblast proliferation and differentiation[J]. Sci Rep. 2016, 6. doi: 10.1038/srep27904.

[40] JIA X, OUYANG H, ABDALLA B A, et al. miR-16 controls myoblast proliferation and apoptosis through directly suppressing Bcl2 and FOXO1 activities[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech, 2017, 1860(6): 674-684. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.02.010

[41] JIA X, LIN H, NIE Q, et al. A short insertion mutation disrupts genesis of miR-16 and causes increased body weight in domesticated chicken[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6. doi: 10.1038/srep36433.

[42] YANG Y L, LOH K S, LIOU B Y, et al. SESN-1 is a positive regulator of lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans[J]. Exp Gerontol, 2013, 48(3): 371-379. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.12.011

[43] EL HUSSEINI N, HALES B F. The roles of P53 and its family proteins, P63 and P73, in the DNA damage stress response in organogenesis stage mouse embryos[J]. Toxicol Sci, 2018, 162(2): 439-449. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx270

[44] CAI B, MA M, CHEN B, et al. MiR-16-5p targets SESN1 to regulate the p53 signaling pathway, affecting myoblast proliferation and apoptosis, and is involved in myoblast differentiation[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0403-6.

[45] CABILI M N, TRAPNELL C, GOFF L, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses[J]. Genes Dev, 2011, 25(18): 1915-1927.

[46] OKAZAKI Y, FURUNO M, KASUKAWA T, et al. Analysis of the mouse transcriptome based on functional annotation of 60, 770 full-length cDNAs[J]. Nature, 2002, 420(6915): 563-573. doi: 10.1038/nature01266

[47] WILUSZ J E, SUNWOO H, SPECTOR D L. Long noncoding RNAs: Functional surprises from the RNA world[J]. Genes Dev, 2009, 23(13): 1494-1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909

[48] SANLI I, LALEVÉE S, CAMMISA M, et al. Meg3 non-coding RNA expression controls imprinting by preventing transcriptional upregulation in cis[J]. Cell Rep, 2018, 23(2): 337-348. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.044

[49] KALLEN A N, ZHOU X B, XU J, et al. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs[J]. Mol Cell, 2013, 52(1): 101-112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027

[50] ZHOU L, SUN K, ZHAO Y, et al. Linc-YY1 promotes myogenic differentiation and muscle regeneration through an interaction with the transcription factor YY1[J]. Nat Commun, 2015, 6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10026.

[51] LI T, WANG S, WU R, et al. Identification of long non-protein coding RNAs in chicken skeletal muscle using next generation sequencing[J]. Genomics, 2012, 99(5): 292-298. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.02.003

[52] LI Z, OUYANG H, ZHENG M, et al. Integrated analysis of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and mRNA expression profiles reveals the potential role of lncRNAs in skeletal muscle development of the chicken[J]. Front Physiol, 2017, 7. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00687.

[53] OUYANG H, WANG Z, CHEN X, et al. Proteomic analysis of chicken skeletal muscle during embryonic development[J]. Front Physiol, 2017, 8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00281.

[54] LI Z, CAI B, ABDALLA B A, et al. LncIRS1 controls muscle atrophy via sponging miR-15 family to activate IGF1-PI3K/AKT pathway[J]. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle, 2019, 10(2): 391-410. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.v10.2

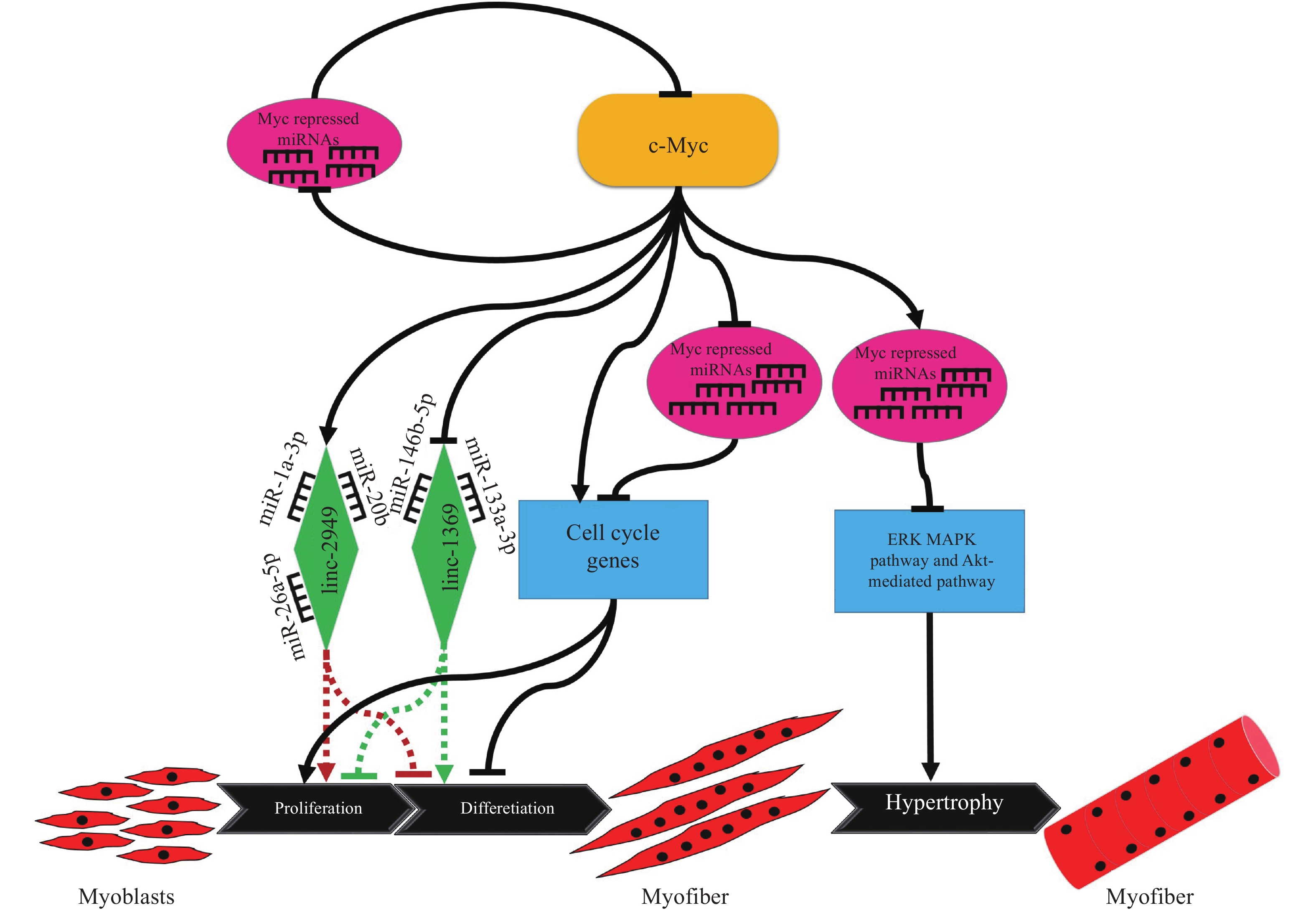

[55] LUO W, CHEN J, LI L, et al. c-Myc inhibits myoblast differentiation and promotes myoblast proliferation and muscle fibre hypertrophy by regulating the expression of its target genes, miRNAs and lincRNAs[J]. Cell Death Differ, 2019, 26(3): 426-442. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0129-0

[56] CAI B, LI Z, MA M, et al. LncRNA-Six1 encodes a micropeptide to activate Six1 in cis and is involved in cell proliferation and muscle growth[J]. Front Physiol, 2017, 8. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00230.

[57] MA M, CAI B, JIANG L, et al. LncRNA-Six1 is a target of miR-1611 that functions as a ceRNA to regulate Six1 protein expression and fiber type switching in chicken myogenesis[J]. Cells, 2018, 7(12). doi: 10.3390/cells7120243.

[58] DANAN M, SCHWARTZ S, EDELHEIT S, et al. Transcriptome-wide discovery of circular RNAs in archaea[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2012, 40(7): 3131-3142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1009

[59] CHEN L L, YANG L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis[J]. RNA Biol, 2015, 12(4): 381-388. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1020271

[60] ENUKA Y, LAURIOLA M, FELDMAN M E, et al. Circular RNAs are long-lived and display only minimal early alterations in response to a growth factor[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016, 44(3): 1370-1383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1367

[61] WU Q, WANG Y, CAO M, et al. Homology-independent discovery of replicating pathogenic circular RNAs by deep sequencing and a new computational algorithm[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(10): 3938-3943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117815109

[62] LEGNINI I, DI TIMOTEO G, ROSSI F, et al. Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis[J]. Mol Cell, 2017, 66(1): 22-37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.017

[63] HANSEN T B, JENSEN T I, CLAUSEN B H, et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges[J]. Nature, 2013, 495(7441): 384-388. doi: 10.1038/nature11993

[64] MEMCZAK S, JENS M, ELEFSINIOTI A, et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency[J]. Nature, 2013, 495(7441): 333-338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928

[65] DU W W, YANG W, LIU E, et al. Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016, 44(6): 2846-2858. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw027

[66] OUYANG H, CHEN X, LI W, et al. Circular RNA circSVIL promotes myoblast proliferation and differentiation by sponging miR-203 in chicken[J]. Front Genet, 2018, 9. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00172.

[67] CHEN X, OUYANG H, WANG Z, et al. A novel circular RNA generated by FGFR2 gene promotes myoblast proliferation and differentiation by sponging miR-133a-5p and miR-29b-1-5p[J]. Cells, 2018, 7(11). doi: 10.3390/cells7110199.

[68] CHEN B, YU J, GUO L, et al. Circular RNA circHIPK3 promotes the proliferation and differentiation of chicken myoblast cells by sponging miR-30a-3p[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(2). doi: 10.3390/cells8020177.

-

期刊类型引用(4)

1. 戴娜桑. 当前福建省南安市猪繁殖与呼吸综合征病毒的遗传进化分析. 中国兽医卫生. 2025(01): 15-21 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 覃珍珍,王志远,文波,潘红丽,凌洪,郑蓉,吴先华. 我国猪繁殖与呼吸综合征病毒ORF5基因变异及全基因组重组分析. 中国猪业. 2024(06): 66-75 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 于海丽,陶伟杰,刘佳卉,单虎,杨海燕,张传美. 仔猪PRRSV和PCV2混合感染的诊断及病毒基因型分析. 动物医学进展. 2022(06): 119-124 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 张帅,赵云环,刘莹,翟刚,郭禹,刘涛,左玉柱,范京惠. 基于PRRSV ORF5基因TaqMan qPCR检测方法的建立及遗传变异分析. 中国兽医学报. 2022(06): 1122-1130 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

下载:

下载: